“Before and After Mexico” by Bruce Sterling (2010)

Foreword: I don’t say much here on lively, bustling Medium, so I’ve decided to release a work of science fiction, just to see what, if anything, happens.

This story of mine was commissioned by Pepe Rojo and Bernardo “Bef” Fernandez for their Mexican-themed ciencia ficción collection, “25 minutos en el futuro. Nueva ciencia ficción norteamericana.” Of course it appeared in Spanish, and has never before been seen in English.

I’m grateful to Pepe and Bef for the chance to touch on these themes.

Bruce Sterling

Before and After Mexico

by Bruce Sterling

The Pueblo braves signalled with the mimicked cries of blue-jays. Bowl Owl called back to them, not wanting to be shot.

At the bottom of the canyon was a sump that offered muddy water. This was a death-trap. Here, the Pueblo militia ambushed the thieves of the Skullbasher tribes.

The Skullbashers were nomadic horsemen. They lived off roaming herds of wild longhorn cattle. Sometimes they left their palamino mustangs, to climb bow-legged into Garden Canyon, to steal the corn and beans of the cliff-dwellers.

The Skullbashers commonly died trying this wicked thing, because the cliff-dwellers of Garden Canyon Pueblo were a people of deep forethought and historical philosophy. The invaders would die, but time would pass and new Skullbasher braves would arrive in the canyon. They were eager to scale the cliffs, kill the men, rape the women and abduct the children.

Therefore, every child in Garden Canyon knew nursery songs about the pueblo’s caves, strong-houses, and secret hide-aways. Also, there were many trail bends, where even small Pueblo children could tip big lethal rocks onto the heads of unwary intruders.

Today, a different prey had fallen into the Pueblo’s ambush trap. As Bowl Owl drew near, an enormous beast was dying in the waterhole, splashing and bellowing in anguish, in a slimy pit of trampled mud and its own shed gore. It was a bison, a great hoofed and horned brute, bristling with Pueblo arrows and buzzing in a cloud of flies.

Hatchet Falcon, the war chief, had command of the situation. A half dozen of his men were preparing to butcher the creature, using the sharp edges of freshly broken cobblestones. Another half-dozen braves lurked within the thickets with bows, slings and spears, in case any Skullbashers noticed the gathering vultures over the kill.

Hatchet Falcon offered Bowl Owl a casual salute. Hatchet Falcon was of the military fraternity while Bowl Owl, a scholar, was not. “First that volcano, and now this damned bison appears,” said the warlord. “Bowl Owl, what have we failed to foresee?”

Bowl Owl observed and inspected the gory scene. The braves of the pueblo had never much impressed him. They wore gaudy war paint and carried costly shields, stone axes and cane bows, but the soldiery were the pueblo’s scarred and tattooed desperadoes. Men like them would never settle down to an honest living. It took mean-tempered disciplinarians like Hatchet Falcon to manage such rascals.

“I can foresee,” Bowl Owl told him, “that there is fresh meat for the people, and I congratulate you. As for the volcano, the erupting mountain is indeed of great concern. The danger is grave, but not immediate. That volcano is almost as far away to the north as Mexico is to the south.”

“Am I a small child, wise man?” said Hatchet Falcon. “Don’t soft-talk a man-at-arms about the threats to our community! What if the volcano’s ashes smother our crops? What if an earthquake sends a cliff-house tumbling into the valley?”

Since these were exactly his own private worries, Bowl Owl wisely said nothing.

“As for the Mexicans, the Mexicans are much closer than you know! They could march an expedition up here and impose haciendas and estancias! They might even bring their churches!”

“The Mexicans come and go with time, general,” counseled Bowl Owl, for the military was always carrying on about the Mexicans. “Our canyon community has limited resources. If we put ourselves on a permanent war footing, then the weak will hunger. Your militia needs strong young men, not starving children.”

Hatchet Falcon rolled his hooded eyes below his fringed leather war-hat. “Oh, spare me your windy peace talk! You claim you’re a practical man, Bowl Owl, but you never face danger forthrightly! All you scientists ever do is spout big words, stall for time, and demand more research.”

“Rashness is unwise. The Great Spiral Calendar brings us each change of events at the proper pace.”

“You know very well what I’m talking about,” said Hatchet Falcon, who was a hardened man. “Five years ago, Bow Eagle quarreled with Mirror Serpent, and you know why, too. If you had let those two hot-heads fight it out fair and square, we’d know where we stand today.”

“You think Bow Eagle would have won.”

“Of course Bow Eagle would have killed Mirror Serpent! I trained Bow Eagle in combat myself.”

“I trained Mirror Serpent. A wily youth. Extremely intelligent. He might have prevailed in some more subtle way, and then you would have no militia. Instead of slaying this bison in a glorious feat of arms, you’d be passing out hot beans in a fancy costume as the CornWaterMan.”

Hatchet Falcon silently scowled. One of Hatchet Falcon’s men brought him a large bloody chunk of the bison’s raw liver.

Hatchet Falcon took a thoughtful bite. “You’re right, it is a glorious feat of arms,” he said, and smiled. “That beast out-weighs fifteen of my men! There’s also the hide, the hoofs, the horns and the bones to consider! Not a bad morning’s work.” With his bowstring-hardened fingers, he pinched off a small chunk of the liver and handed it to Bowl Owl.

Bowl Owl munched and swallowed. “A magnificent prize! The council must hear this good news. I lack the eloquence to describe your great feat. Please see fit to tell them yourself.”

“There’s no need for your blabbering and jabbering in the council kiva,” said Hatchet Falcon uneasily. “This a military capture, so it’s a military requisition. Simple as that. This meat should be cut up, smoked and distributed among my troops as their trail rations.”

“You overlook the tripe and the marrow,” Bowl Owl pointed out. “Also, this beast’s hide and head deserve a glorious display in the great plaza, next to the Great Spiral Calendar. The people must understand that history moves in spirals, which is why the bison have returned to us in this way.”

Hatchet Falcon, who was sadly literal-minded, scratched his braids below his war-cap. “We never killed any bison at this waterhole before just now.”

“I was pondering the future, general. Even more bison might return. Since a bison has wandered this far into our canyon — past miles of landslides and boulder-fields — there must be other bison nearby. We should mount an expedition to search for the herd.”

“I didn’t think about an entire herd of thirsty bison,” said Hatchet Falcon. “But you’re right.”

“Someone must explain the need for swift action. If your men could bag five of these beasts, we’d have no more fear of crop failure this year. With ten of them, we could survive for two winters.”

“Excellent,” said Hatchet Falcon, loosening the stone axe in his braided belt. “It’s a good thing to hear when a scientist talks simple common sense.”

#

The night’s council meeting went well. Bowl Owl said not one word, but he had arranged the agenda. The ceremony opened with a humble little song by Flake Raccoon — touchingly accompanied by his mother with a drum, and his cute little sister with a cedar flute. The farm boy’s folk song was all about the many uses of the herb “rabbitbrush,” and this song taught the young people new things, and helped the old people remember old things.

After the farming song, the war chief Hatchet Falcon spoke to a large crowd. A big hunting success was always popular news. His men were rewarded with turquoise beads. The bravest was promised a wife.

It had long been speculated, or rather predicted, that the bison would someday return to the canyon. History moved in spirals. The long-horned cattle had been brought to the land by the Mexicans, a volatile people who also moved in spirals. However, the bison were much older than the Mexicans. The bison were native to the landscape, like the sandstone and the yucca. So when culture collapsed, and when governments faded, the bison would be back.

This spiralling return of the old was always magnificent news for the people of Garden Canyon Pueblo. Being placed at the center of the universe, they didn’t spiral much themselves. Instead, they managed events, and often did that well. The bison abounded with meat — so much that the CornWaterMan added slivers of bison fat to his charity corn and beans.

The people danced and sang after the successful council meeting. Later, from every slope of the canyon, people left their narrow stone barracks in the cliffside caves. They came in family groups to admire the severed bison head. This massive trophy sat oozing blood over the stone base of the Great Spiral Calendar. In torchlight, it made a fine thing to admire.

The CornWaterMan, who never spoke, brought his tall clay stove to the plaza. He passed out his ancient black-and-white bowls of corn and beans, and his smaller bowls of ritual herb tea. The CornWaterMan wore stilted clog shoes, and stiff, checkered robes, and a slit-eyed wooden helmet fringed with tall parrot feathers. The CornWaterMan fed the lost souls in the canyon. This was his purpose. He fed the poor, the desperate, the drunks, the foreigners, the crying scolded child, anyone for whom life was too hard.

In easy times, the silent CornWaterMan was easy to overlook. In hard times, he was the most important man. Hard times were always coming to the pueblo, some day. It was already hard times, somewhere, for some poor body.

Bowl Owl was, by his own shrewd reckoning, the most powerful chief in the pueblo. He nevertheless bowed before the CornWaterMan. The “CornWaterMan” was not a mere mortal man like Bowl Owl. He was an office that outlasted the centuries, as the corn did, as the water did.

Bowl Owl was the servant of the people. He was the Master of Seed Lore, and he knew all of the one hundred and seventy nine songs that described the many useful plants in Garden Canyon. With so much scientific wisdom in his head, Bowl Owl found it hard to be a simple man. It was harder to be a clear man, speaking only the truth to people. It was hardest of all to lead the people into the future, and yet also be an invisible man.

This was the great quality that Bowl Owl aspired to share with his colleague, the CornWaterMan.

The people of Garden Canyon Pueblo were a wary, watchful, and much-experienced folk. Their magnificent canyon was narrow and arid, although old and strong as rock. The skills they had to survive there were precious, precarious skills. Bowl Owl knew that they were fretting about the bison expedition.

Bowl Owl often called on the people of Garden Canyon for expeditions. The pueblo had to try these experiments, lest they be surprised by events outside their beloved, colossal stone walls. But the people hated the risk, and begrudged the lost resources. Bowl Owl had to take care.

The world outside Garden Canyon was unrelentingly hostile. To the north were vast, fatal deserts, and, worse, there were certain other canyons, featuring smaller, rival cliff-dwelling societies, mere cave-men who were nowhere near so advanced and intelligent as the Garden Canyon people.

To the west roamed the ferocious Skullbasher horse tribes, and past them their brutal rivals the Mountain Cannibals, and then, far away, at the seaside, the worst of them all, the Californians.

To the east, there were great grassy plains infested with the Stake People and the Sod People and the Longhouse People. These indigenes were not quite so fierce and evil as the Skullbashers, but they had incomprehensible languages, bizarre rituals and unfortunate skin colors.

To the south, of course, there was Mexico. Mexico was a turbulent place that ceaselessly bred great civilizations. A vast, unstable, untrustworthy realm, where stone city-states ruled by priest-kings sprawled across fertile river valleys, with roads, bridges, and huge networks of canals. The Mexicans never understood the clean and simple truth about Great Spiral Calendars. The Mexicans had their own kinds of round stone calendars, which were superstitious and useless.

Of all the many enemies of the Garden Canyon Pueblo, the Mexicans were by far the most troubling threat. The Mexicans had infectious diseases, an army, steel weapons and a written language. The Garden Canyon Pueblo had none of those amazing and terrible Mexican things, and did not ever want to see them.

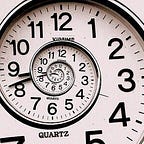

Every morning in Garden Canyon Pueblo, the costumed cult of Clock Men would re-set the canyon’s Great Spiral Calendar. They would spin its many concentric stone rings, and the mythic symbols carved on the rings would exchange positions.

Then everything would change so that everything could remain the same, and Bowl Owl knew that this was good. This had been good, and it would remain good, and it was in some sense the definition of good. It was optimal, it was pragmatic, it was canyon life as it should be. However, mankind had a tragic dimension.

When the ambitious factions of Bow Eagle and Mirror Serpent had come to blows, disaster loomed for the community. Then Bowl Owl had intervened. The two fiery leaders and their closest disciples had been banished on two different expeditions. The council had decreed that each man should explore the world outside — and take care not to return to the Garden Canyon Pueblo for five long years.

Tempers had cooled in the five years since then, as tempers did. Since there had been no word from Bow Eagle or Mirror Serpent — nothing but wild foreign rumors — it could be safely assumed that they were both dead.

Bowl Owl felt grave sorrow for this sly but necessary deed. He had sent two of the pueblo’s best and brightest men to their deaths, while disguising that as a civic duty. He mourned them both sincerely. Bow Eagle had had every virtue that a warrior brave should possess — courage, striking good looks, shrewdness, and good judgment about fighting men. Mirror Serpent was a brilliant scholar, imaginative, inquisitive, observant, untroubled by prejudice, and tenacious of memory.

Unfortunately, these two grandiose figures were too big of soul for their small, conservative community. Worst yet, having taken each other’s measure, they hated each other. So they were forced to depart the pueblo, to the grief of their families, and the especial resentment of Bow Eagle’s widow, the prettiest woman in the canyon.

Given time, Bowl Owl might have found a way to forgive himself. After all, a leader’s merits did not lie in doing what he wanted to do, but in doing what history required of him. However, Bowl Owl’s misdeeds were never forgotten by his own wife, Barn Owl.

Barn Owl was a woman of local prominence. She had been of great help to Bowl Owl in his ascent to power. Barn Owl had also dutifully born him two children, which was laudable. However, Barn Owl had never forgotten, or forgiven, the many silent sacrifices that a political wife had to make.

“Look at these rafters hung with bison meat, you scheming rascal,” Barn Owl complained, in the reeking depths of her stony kitchen warren. Barn Owl never much cared when they were overheard by others. “Your ruffians kill that stinking monster of a malformed cow, and who has to cook it? Me, of course!”

“This is your laboratory! Who else can assure us that bison is safe to eat?”

“No word of warning to me? No please or thank you? And now you want more bison killed and cured? Where’s the salt for all that?” Barn Owl stoked a smoking chimney-stove with one hand, while rocking her grandson’s headboard with another. “Do you think that my science lab does nothing for the people all day? What are we supposed to do about the foodstuffs mandated by the calendar?”

“Be reasonable! The people ate well yesterday, they’re rejoicing! Everyone’s happy but you!”

“You conniving wretch! They ate cuts of meat I stole from the army! When will your egg-head scientists speak up for themselves? They’re always treacherous weaklings!”

“My dear, you know that the scientists are jealous of the army! Especially when a general parades a hunting triumph in front of everybody! It’s more tactful that way. It saves face.”

“It doesn’t save my face!” cried Barn Owl, groping at the striped greasepaint on her plump cheeks. “Being the wife of Bowl Owl, I have no face! Your crimes go unseen because I’m the one doing them for you!”

Bowl Owl knew that he should say nothing — because she was telling the truth. Unfortunately he had never managed the feat of keeping silence with Barn Owl. “Is there something I can do to fix things for you?” he offered at last. “Can’t you just tell me what you need me to do?”

“I never wanted to be become the head chef in this food laboratory,” Barn Owl lied. “You made me do that.”

“It made sense! It perfectly complements my mastery of the lore of seeds and crops. Look how plump you are, now that you’re fifty years old! You’re better fed than any other woman your age.”

“Why don’t you bring your Mexican girlfriend in here, and have her fix my kitchen?”

Bowl Owl sighed and sat on the cold stone floor. It always came to this, and it always weakened his knees. “I had to go on that embassy to Mexico. I had to pay them their tribute, to persuade them not attack us. I was young in Mexico, I was far away from home for a long time. A young man has his needs. I made a mistake. I’m not the CornWaterMan, I’m not a demigod.”

“I never asked you to become a demigod, don’t flatter yourself! I only asked that you should obey our marriage vows, which you swore by the Great Spiral Calendar.”

“Time changes everything! Imagine that I had set you aside when you got old, and taken a younger and prettier wife, and sired new children with her! Wouldn’t that be much worse of me?”

“There is no possible limit to how bad you are! You can twist things into spirals just by looking at them.”

“Fine, sure, Barnie! Kill me here, chop me up, put me in a pepper soup! Why must we have the same quarrel a thousand times over? Nothing ever changes with you.”

Barn Owl wiped at her eyes. “Well, if I have to cook a bison, then you had better give me help.”

“All right. Just say it. What do you need?”

“I’m a grandmother now, I’m being worked to death in here! Let someone else pay heed to all your great traditions.”

“Do you have a proper successor in mind for your post as chief of foodstuff certification?”

She shrugged. “Our daughter-in-law can cook.”

Bowl Owl was unsurprised by this development. His daughter-in-law cooked well enough, but only because Barn Owl nagged her relentlessly. His son’s wife was meek, weak-minded and dutiful, nothing like a proper scientist. In this, she suited his son, who, being the child of Barn Owl, was not much brighter than his mother or his spouse.

“This pueblo laboratory is a serious enterprise requiring great practical knowledge,” stated Bowl Owl. “Our daughter-in-law, whom we both love dearly, is too young.”

“Look at this avalanche of meat! And more bison coming, you say! Suppose that I lie down sick?” said Barn Owl. “Let the meat rot, that will show you.”

“Don’t be like that, Barn Owl. When the people go hungry it’s sinful.”

“Cook a herd of bison yourself, since you’re so clever.”

A sudden desperation seized Bowl Owl. He was trapped by historical guilt. He had committed a great sin of long-lasting, ever-returning consequence.

He knew that he should never have made a mistress of the Mexican girl. All of his troubles at home had followed from that Mexican adventure. He had pretended reluctance to go to Mexico, but he had gone because he was so curious. A scientist wanted to see the world with his own eyes, and weigh evidence for himself, and test it. That was what science was.

In Mexico, he had seen that Barn Owl was a short, portly creature united to him in an arranged marriage, while his Mexican courtesan mistress, Pyramid Parakeet Yam Misty Obsidian, was a big-city girl. She was a dreamlike, willowy, sophisticated creature, with a tight girdle, jade earplugs, and red coral hairpins. When it came to what a woman could do for a man, Barn Owl was like the dim corner of a small stone blockhouse, while Pyramid Parakeet Yam Misty Obsidian was a sunny plaza in a seething city where young men were chopped to pieces on the vermilion steps of a pyramid and devoured in eager gulps by the multitude.

No man who lived in a cliff-dwelling could explain Mexico to a woman.

#

The military expedition returned after their brief hunting spree. They had tracked a small herd of bison, cropping the thin grass and exiting the region. They had killed two bison cows, at the cost of one young man crippled for life.

This was a bitter price, but also a heap of meat, and the pueblo of Garden Canyon slept the sleep of the fortunate.

In the morning the village woke to a shattering noise, a trail of smoke, and a burst of fire in the sky.

The exiled cult leader, Mirror Serpent, had returned from his own expedition, after five years of absence.

In fact, it was not quite five years, for Mirror Serpent had arrived one week early. Rather than apologizing for his breach of propriety, though, Mirror Serpent alleged that the Clock Men had made an error in their mathematics.

According to this sturdy young scientist, the Clock Men had grown sloppy while protected by their sinecure. It was he, Mirror Serpent, who, despite his perilous life of exile, had stayed true to the facts of the stars.

Mirror Serpent had departed as a quarrelsome intriguer, but he returned to Garden Canyon as a wizard. Four of the six acolytes from his expedition were just as alive as himself. All of them were rich men. They led a string of donkeys — real beasts of burden, unknown on the cliffs — donkeys that were heaped with bags of sea-salt and many precious shells. The exiles even had their own caravan guards, two wild-eyed savage cannibals standing seven feet high, from the unmapped coasts of Texas.

Cavalierly tossing small bags of precious salt to his people, Mirror Serpent casually mentioned the many caches of treasure he had buried along his way.

His story spread throughout the canyon like a wildfire. Mirror Serpent had not just survived, but prevailed. He had convinced the credulous tribes to the east that he was a medicine man of great power. Mirror Serpent did know quite a lot of Garden Canyon science: about stars, pottery, water storage, looms, and herbal lore.

Sharp eyed and observant, Mirror Serpent made an excellent doctor. So he’d migrated for five years, unharmed, from tribe to savage tribe, never outlasting his welcome, and finally venturing all the way to the ocean, then back to his desert.

Learning the trade routes and the many needs of the locals, Mirror Serpent had prospered. He’d ingratiated himself with the other medicine men of many tribes — especially the Pepper Paper People. These friendly Texans lived in pit-houses and limestone bunkers amid a series of creeks.

The Pepper Paper People cordially welcomed the emissaries of the Garden Canyon culture. Seeing the kinship that their cultures shared, they had practically adopted Mirror Serpent and his small expedition. The hosts and guests happily spent months together, trading arcane lore about the days of the Lost Old Ones, such as the truth about atoms, and where to look for ancient satellites tumbling down from the sky.

The Pepper Paper People did have their faults, said Mirror Serpent, for they were soft and fat and contented folk, and they worshipped a horned god who required them to play enormous, useless ball games. Such a naturally lazy people were not worthy of the leadership of Mirror Serpent. He aspired to lead a time-tested, virtuous people of superior wisdom.

He climaxed his appeal with a series of amazing explosions that half-deafened his listeners and left the kiva shaking.

It was natural for Mirror Serpent to be acclaimed as the Chief Medicine Man of Garden Canyon. Mirror Serpent had always aspired to this post of supreme scientific authority. Unfortunately, the rude antics of his rival Bow Eagle had postponed his rise to eminence. Now he was rich, while Bow Eagle was dead. Destiny had spoken.

On a technicality, Bowl Owl managed to postpone Mirror Serpent’s triumph for a week — until the full five years of his exile had fully, officially passed. But Mirror Serpent was not deceived or denied by any delaying tactic. He used the spare hours to consummate a lightning courtship with the pretty widow of Bow Eagle.

Bow Eagle’s widow, Loom Eagle, had always been the belle of the pueblo. She was given to tight deerskin suits lavished with embroidered beads, and always wore a diadem of feathers. Mirror Serpent had long lusted after the flirtatious wife of his rival. So did every other man in the canyon; but Mirror Serpent offered a dowry of pearls and seashells that made Loom Eagle the richest woman in living memory.

After his swift courtship and his consummated marriage, Mirror Serpent and his lieutenants really set to work. His first effort as Chief Medicine Man was calendar reform.

All the Clock Men were relieved of office, and replaced with Mirror Serpent’s trusted followers. These new astronomers pulled the stone calendar from its mounting, pried loose its concentric rings, washed the rings, oiled them, and then reassembled the totem.

The new Clock Men explained that, due to stellar mathematics that only they understood, the Spiral Calendar had been moving far too slowly. That was why the Pueblo people had been lazing in the sun, dull of mind and half-starved, for years, instead of eating properly, working through the heat of the day, and generally setting an example for the lesser folk.

With the calendar reformed, Mirror Serpent turned his attention to the pueblo’s water policy.

It was the harsh discipline of water that had made the people of Garden Canyon such intelligent, foresighted folk. Thanks to the pueblo’s careful stockpiles of bulbous water jars, they flourished in their dry death-trap of a canyon while their enemies commonly died of thirst.

Mirror Serpent understood all this, but he also repaired and extended the pueblo’s water system, building new check-dams, aqueducts, tanks and cisterns. He also took care to attack and poison all the sources of potable water within fifty miles.

No Pueblo leader had tried that strategy before. Soon the fierce Skullbashers, and also their prey the wild longhorn cattle, were dying like flies. With the threat to his realm defeated, Mirror Serpent demobilized the pueblo militia. He reassigned the soldiers to improve agricultural productivity.

Month by month, progressively, Mirror Serpent’s inventive policies bore fruit. With food and water plentiful and a lasting peace at hand, the pueblo cliffs flourished as never before. Flowers sprouted. The public baths and the fountain were immensely popular. People even dared to farm the bottom of the valley.

In the second year of Mirror Serpent’s reign, the grumbling volcano erupted with great force. This long-feared disaster sent a terrifying plume of smoke into the sky that was visible for hundreds of miles around.

While all around him panicked, wept, ate peyote and stabbed themselves with cactus spines, Mirror Serpent was nothing daunted. He serenely explained that a volcano was merely a mountain vomiting melted rock. However, he also sent emissaries to every tribe that could see the great smoke plume. He told them that if they didn’t obey him, he would make it erupt again.

The savages, many already pitifully dying of thirst, were crushed by superstitious dread. They swore fealty to Mirror Serpent, and took to camping on the fringes of the blossoming canyon, sipping bean soup and humbly breaking rock for a new network of paved roads.

With the Skullbashers tamed and many new roads cut across the arroyos, around the mesas, and through the boulder fields, Garden Canyon began to see trading folk. Mirror Serpent, who had learned to speak several languages during his absence, excelled at trade relations. He built storehouses for industry, and taught people the abacus. The elegant members of his court dressed in fine foreign cotton and linen. His wife Loom Eagle was a queen.

Bowl Owl found himself reduced to a last-ditch, bitter effort to prevent metal from entering the canyon. Every wise man knew that metal was a deadly affliction to mankind. Metal had to be melted with a terrible fire, which required the burning of thousands of precious trees.

The forges and smokestacks of the Old Ones had turned the world to overheated desert. Everyone knew that myth. It was through accepting the desert, and humbly living with nature instead of against nature, that the Garden Canyon people had survived for so many generations.

However, no one excelled Mirror Serpent in a council debate. By now, the great wizard had several foreign advisors — men of learning from distant tribes, who were honest administrators, and loyal to him only.

Using new maps they themselves had assembled, these wise men pointed out that the world was not a desert any more. Once, yes, the world had been a cursed desert suffering a unnatural, terrible heat, but those days were remote ones. In the present days of the spiral of history, thick jungles and dense, gloomy forests grew tall on the forgotten cities of the Old Ones.

These ruins were treasure-dumps of metals. Great wealth awaited an ambitious new breed of scientists, those who could stake a claim to those cities of gold, beyond the horizon.

Mirror Serpent therefore created such an expeditionary force. These science explorers were actually the same old Pueblo militia. However, with their new surveying tools and new officers, they were loyal to him.

At this point, Bowl Owl saw that events had escaped his grasp. He was desperate. Month by month, week by week, Bowl Owl was becoming yesterday’s man. Bowl Owl was still honored as the Master of Seed Lore, but Mirror Serpent had imported new crops. These bizarre anomalies — pecans, grapefruit, oranges, lemons and the weirdest of them all, bananas — were extremely tasty and deservedly popular.

Bowl Owl was forced to conspire with his son, the last man he could trust. Bowl Owl’s son had been given the name Spoon Peccary. He was kindly, meant well and had a good heart.

Spoon Peccary, whenever fed by his wife or his mother, was willing to sit and eat, then listen obediently as Bowl Owl tested desperate ideas.

How was the dishonored Spiral Calendar to be restored to the old way? How was the heretic regime of Mirror Serpent to be overthrown? Who could dissuade the pueblo from new foods, hot baths, fine fabrics, efficient tools? Most seductive of all was the growing power that the community held over wretched enemies like the Skullbashers.

How could the people be persuaded to return to their dry, dim, dusty lives in small stone chambers, where families shared a few flea-infested rugs and numbered every pepper and tortilla?

Bowl Owl had always striven to prevent a civil war. Worse yet, he knew he couldn’t win one. Bowl Owl was well-respected, but only a tiny minority spoke out against the great Mirror Serpent. These few complainers were the mulish outcasts who always complained about everything.

Perhaps it would be a sounder idea to emigrate. Leave Garden Canyon to its errors, and find some similar yet different canyon, where a few brave followers could pioneer a new life on the old principles. But — imagine the danger, privation and difficulty of a small cliff colony, with nothing but raw rock and no water jars! What if hordes of savages attacked the tiny group?

Perhaps it would be a good idea to outdo Mirror Serpent at his own game. Leave the pueblo to lead a brave expedition, this time to the North or the West, instead of the East or the South. Some day, Bowl Owl would return in great honor. In the meantime, Mirror Serpent would destroy himself with his arrogance and ambition. Then Bowl Owl could bring back the old way of life to the chastened followers of the dead revolutionary. In short, the situation would spiral around.

But was this scheme plausible? Wasn’t it just an empty revenge fantasy? Bowl Owl was an older man with settled habits. In exploring a trackless wilderness he would likely freeze, starve or be scalped.

Perhaps the best method of resistance would be to set a personal moral example. Although he lived within the pueblo, surrounded by its decay, Bowl Owl could simply, defiantly, and openly adhere to the strict old ways. He could sing songs about his devotion to living in truth, and refuse to use the lying and deceptive words of Mirror Serpent. He could refuse the new foods. Avoid the new roads. Count by the traditional calendar. He could condemn the exceedingly popular, gaudy and indecent clothing of Loom Eagle, who was really becoming insufferable.

But if Bowl Owl singled himself out in this way — becoming a spectacle through moral example — wouldn’t he open himself to ridicule? He had the reputation of an eminently reasonable man, while most self-appointed saints were cranks mocked even by small children.

A saint had to resist a great evil to win credibility. What had Mirror Serpent ever done to make himself loathsome to the people? He’d merely staked out a few Skullbasher braves over anthills, and that was just to show them he was serious. Mirror Serpent did not aspire to become a hateful tyrant. Mirror Serpent considered himself a sincere truth-seeker firmly allied to the forces of nature.

The truth was that Mirror Serpent had won the respect and admiration of all Garden Canyon. Since the people applauded him, none of their hands were clean. They had all collaborated in his scheme to pervert their traditions. When the calendar stone spun madly under his new regime, they gazed on with a pleased indifference and went on eating bananas.

If the mad leader should rightly be punished, then the people deserved punishment as well. This dark prospect preyed on Bowl Owl’s imagination. The Master of Seed Lore knew where they kept the water jars in Garden Canyon. Certain plant poisons dripped in that water would cut the population in half.

Half a generation would perish, but the canyon tradition would revive, and survive. What was any one human generation? Just a spin of the calendar wheel. Except for the count of the dead, would this act of many deaths be any different, morally, than a lone man drinking himself to death? Something that Bowl Owl was sorely tempted to do?

Surely, surrender was an option, too. Just give up. Leave public life, abandon destiny to others, stay at home in a dark room, sing the old songs, drink pulque, smoke, eat peyote until his mind went and his hair was caked with dirt. That would show the ingrates.

“You’re drunk now, dad,” Spoon Peccary remarked. “You are raving, and that’s not like you. What’s so bad about what we do in Garden Canyon? We’re just people! We make some mistakes, so what? What about the Mexicans? The Mexicans are people, too, and they’re a lot worse than we are. Because there are lots more of them.”

“Oh, if only! If only Mirror Serpent had gone south to the Mexicans, instead of east to those crazy Texans! The Mexicans would have eaten him like a chihuahua dog with pepper sauce. How I wish Bow Eagle had returned to us, instead of that sorcerer! Bow Eagle had spirit and honor, he had a decent soul. Life would have been tough, but at least he would have made his wife behave.”

#

Slowly, Bowl Owl convinced himself to destroy the tyrant at the cost of his own life. His own life was temporary. Most of his lifetime had passed already with the turning of the calendar’s stone wheels. To surrender his life to save the precious calendar would be a great honor. So Bowl Owl would creep upon the pueblo’s leader secretly, and stab him to death as he slept.

But this was such a dreadful act of cowardly treachery. After such an unmanly deed, no one in Garden Canyon would ever combine the names “Bowl” and “Owl” again. The memories of his favorite implement, and his spirit animal, would both be tainted for the ages.

Before Bowl Owl could nerve himself to take action, the rains came. The rains were a mighty deluge, more lush and generous than the desert had seen in decades. The sands exploded with fragrant poppies. Stony, all-enduring frogs emerged from muddy ponds. Mesquites that seemed deader than mummies sent out green fronds. All the volcanic ash melted away to enrich the dampened soil. Then, even the humblest terraces gave forth with bee-weed, bottle gourds, cliff roses, ricegrass, squash and sunflowers.

With life so sweet and easy, it was startling to see the Garden Canyon Pueblo suddenly seized by the troops of Bow Eagle.

The warrior exile had sworn to return to Garden Canyon Pueblo after five years. However — as he explained in council — he had had to wait for decent rains in order to provide fodder for his cavalry.

Bow Eagle had ventured south into Mexico. To while away the five years of his exile, he had sworn his fealty there to the God-King of Crater Lake City. Crater Lake City was the nearest and strongest metropolis among the many royal cities of Mexico.

Bow Eagle’s cunning and ambition had served him well in Mexico. As the native of a hard land, he had excelled at repressing the desert enemies of the God-King. He’d even besieged and conquered several lesser city-states in Mexico, winning such honor and glory that the aging God-King had given him his own daughter to wife.

Of course, by Pueblo tradition, Bow Eagle was already married to his Garden Canyon bride, Loom Eagle. However — as he explained to his former compatriots — their merely local laws no longer applied to him, an imperial conquistador.

As a Mexican warrior-prince allied to the royal family, Bow Eagle had abandoned his humble, workaday Pueblo identity. In Mexico he was known to all as Generalissimo Flame Flint Condor.

His royal bride had accompanied him on his surprise march across the desert. The new wife of Bow Eagle was the God-Princess Orchid Jade Quetzal Hurricane.

This regal personage had ridden on horseback hundreds of miles, parched by day, frozen by night, and living mostly on hard-tack and jack-rabbits. But, in a spirited defiance of all these hardships, she had arrived in Garden Canyon as the picture of imperial Mexican dignity.

God-Princess Orchid Jade Quetzal Hurricane wore hallucinogenic royal finery: linens, cottons, jaguar hides, feathers, long tattered skirts, fur mantles, jewelled ear-plugs, golden nose rings…. Skulls, claws, inhuman teeth on black leather tethers, vast trailing lengths of false human hair, and a long, black, beaded, sinister necklace with a cross-shaped torture implement.

The Mexican princess had a personal bodyguard of dauntless, bearded cavalrymen with steel lances and steel armor. She did not need these men. The God-Princess Orchid Jade Quetzal Hurricane walked among the simple people of the pueblo as if they had no reason to resist her. Awed by this gorgeous vision — this demigoddess catapulted from blue heaven — they didn’t even know how to try.

Her Highness the Mexican princess showed even more mettle in private than she did on parade in the plaza. God-Princess Orchid Jade Quetzal Hurricane had mastered the language of Garden Canyon. She had learned it from her beloved husband, and also from his many spies.

Bow Eagle soon revealed that Garden Canyon was seething with his secret agents. Chief Medicine Man Mirror Serpent had been too lax, open and trusting. He had allowed traders to come and go as they pleased, and many came and went from Mexico — in the pay of his rival.

The disbanded pueblo militia had always resented Mirror Serpent’s attack on their esprit de corps. When they realized that their former leader Bow Eagle was alive and flourishing, they had sworn secret oaths and joined his secret society.

The wily Mexicans excelled at palace intrigue. The coup plot was hatched, secret bribes were sent to the needful parties, and the Garden Canyon Pueblo had fallen without one arrow shot.

No one had sent any bribes to Bowl Owl. No one had whispered to him that there was a large subversive movement active within Garden Canyon. Bowl Owl’s honesty and integrity were beyond suspicion. No one had dared.

Bow Eagle swiftly rounded up and executed all of Mirror Serpent’s foreign courtiers. After piling their severed heads at the foot of the Spiral Calendar, he explained that they were all spies.

Bow Eagle was a military expert, with the overwhelming advantages of surprise, greater numbers, better weapons, royal prestige, and the willingness to rule by decree. The kiva of the council was closed and locked. Every weak point in the canyon’s defenses was swiftly repaired and put under permanent guard.

Mirror Serpent was captured, bound and concealed within one of the canyon’s secret stony dungeons. Then Bow Eagle, or rather “Flame Flint Condor,” explained the Mexican tradition regarding enemy leaders captured in battle.

The captured Mirror Serpent would be sacrificed — of course, for reasons of state. But not too hastily, for the remote Mexican authorities would have to consult their stone calendars for the proper Mexican astrological conjuncture. Once they sent the word from the throne in Crater Lake City, then Mirror Serpent would be shipped off to the capital, there to be flayed alive in a lavishly horrible and memorable ceremony.

General Flame Flint Condor further decreed that Garden Canyon had always been Mexican territory. Mexican law was clear in this regard. The royal bureaucrats of distant Crater Lake had many maps, deeds, and treaties, demonstrating that the trackless desert had belonged, in both the past and the future, to Mexico.

The people of Garden Canyon had never paid much attention to their region’s abandoned Mexican estancias, haciendas and missions. They lived deep inside ancient canyons, fortified and settled before Mexico and after Mexico.

Now, somehow, they were once again living during Mexico. Garden Canyon was an illegal construction, built without permission in a Mexican land.

After two weeks of this invader occupation, the Clock Men dared to rebel. The Clock Men were the hand-picked partisans of Mirror Serpent, and they saw their prerogatives threatened. Unfortunately, one of them let slip the plot to his wife. This fickle woman had been enchanted by the regal and glamorous Princess Orchid Jade Quetzal. The turncoat warned her beloved princess, and the Clock Men were all seized, bound with thongs, and tossed head-first from a tall precipice.

With the Clock Men murdered, the Spiral Calendar stopped working.

This device was the greatest work of art in Garden Canyon. It was the oldest thing in the canyon, too — older than Mexico, people said.

At the core of the stone calendar was a central stone plug, with the petroglyphs of the Laws of Nature. Outside this core was the sliding stone ring of Culture, adorned with sacred cultural images. Then came the third greased ring of Crafts, where the petroglyphs showed the many tools of daily life.

Then came the stone ring of Governance, which had symbols of power and honor and rule. The Marketplace ring had the petroglyphs of many things people traded and desired.

The final ring of the Spiral Calendar was the biggest, broadest and fastest ring: the Ring of Foolishness. This was the ring that children liked, because it moved back and forth at a touch, and that was funny. Nothing was ever carved in stone on the Ring of Foolishness. The people used chalk on it, and drew whatever they wanted there.

Every day the Clock Men had used their stout wooden poles to rotate the stone rings, so that the petroglyphs lined up in spirals. Then everyone could come and discuss them, so that old things would not be forgotten, and new things would quickly pass by.

That was history, and now history had stopped. It was as if everyone in Garden Canyon was holding their breath.

Somehow life went on.

Flame Flint Condor carried out a few cavalry sweeps of the desert, bringing in some howling, weeping slaves from the remnants of the Skullbasher tribe.

But his rations were running low. General Flame Flint Condor could not maintain an imperial standing army, and especially their hungry horses, in the hutlike barracks and narrow cliff crevices of Garden Canyon. The Mexican troops were restive outside their glamorous capital, being sunburned, thirsty, dusty and deprived.

The warlike Mexicans had seized much “booty” from the pueblo, but since the communal pueblo people owned scarcely anything, the conquistadors had little they could prize. They’d taken stone farming tools, baskets, blankets and pots — the implements needed to sustain daily life.

Soon the people were hungrier than they had been in years. Both the conquered and their captors were forced to forage on yucca roots, jumping mice, beaded lizards and even rabbitbrush seeds.

Doom seemed at hand. Bowl Owl took a certain grim satisfaction in this. The two men he had exiled had both returned, and yet both of them — both! — had more than fulfilled his worst fears about them. Now they had destroyed one another as well as every fine tradition, and their grand pretenses would collapse in fire, blood and starvation.

Bowl Owl secretly began to stockpile seeds — not for the famine, for that was inevitable, but for the time after the famine, when a purged society would begin anew. He even knew what he would say aloud, in council, to the few gaunt and chastened survivors. His speech would be full of bitterness, and they would drink every black drop.

Then God-Princess Orchid Jade Quetzal and her rival, Loom Eagle, somehow saw fit to create a joint initiative. These two women, reasonably, should have killed one another. Everyone expected the worst from their situation. Two spouses of bitter enemies, two beautiful women who had shared the bed of the same man — this should have been a screeching cat-fight with obsidian daggers.

However, an imperial power had supple political methods unknown to mere canyon folk. Princess Orchid Jade forgave Loom Eagle through the expedient of adopting her. The canyon village belle was transformed into Sister-Princess Poppy Cholla Roadrunner Thunderstorm.

“Loom Eagle” was no more, and her former husband “Bow Eagle” was also a nonexistent person. The glamorous new member of the Mexican family, Sister-Princess Poppy Cholla Roadrunner Thunderstorm, was incestuously forbidden to have any relations with her former husband, Generalissimo Flame Flint Condor.

Furthermore, through a gracious royal gesture of dispensation, Princess Poppy Cholla was allowed to re-marry herself to the disgraced local magnate, Mirror Serpent. Royally pardoned, this loyal colonial was to be known simply as Mirror Serpent.

Mirror Serpent emerged from his captivity thin as a wraith, but more clever than ever. He swiftly recognized the straits brought on by Flint Flame Condor’s mismanagement. Without treading on the heels of his new patron, he quietly set his machineries back in order. No word was said about the murdered Clock Men or their abandoned Spiral Calendar. It was tactful to overlook that, since it reflected no credit on either party.

Forced to work together through the good sense of their wives, the two men now saw the folly involved in trying to divide a small pueblo. Their years of exile had matured Mirror Serpent and Flame Flint Condor. Travel had broadened them, too. Why waste such great talents ruling a village of nine hundred souls?

As two rural rivals, they would never achieve grandeur. As a great general allied to a brilliant and capable court intellectual, there was every chance that they could rule Mexico.

The God-King was aging. His heir apparent was a feckless young prince — far less skilled, charming and worldly-wise than his elder sister.

The prince, a minor human obstacle, might well be found drowned in an irrigation canal. Then the General Flame Flint Condor would assume the feathered robes of the God-King. His viceroy and prime minister would be the shrewd Mirror Serpent.

The little-known people of Garden Canyon would become Mexicans. They would not be merely conquered “Mexicans,” but the ruling class of Mexicans. These were the Mexicans that mattered in the world.

There was only one barricade between this dream and its realization: Garden Canyon. Resistant to malice and stonily immune to the centuries, the canyon could never rise to the dimensions of a regal ambition. There just was no room in those narrow, stony crevices. Worse, there was just no water.

To fulfill their manifest Mexican destiny, the people of Garden Canyon would have to pack and up and leave. Silently, and without apparent motive, they would desert their timeless halls of echoing stone. They would forsake the crops, forget the traditions, remove everything portable, and migrate as a people, over the horizon, to a promised land.

What promises Mexico held! A volcanic crater, yes, drenched in blood — but with fresh lake water in plenty, exotic fruits, gorgeous birds, as well as pyramids, palaces, great trading plazas, temples, schools, observatories — everything from mahogany cradles to tombstones.

Once he realized that the doom had truly come for the pueblo, Bowl Owl changed as a human being. He avoided the council, began drinking heavily, taking peyote and even eating the soul-blasting Mexican mushrooms. This behavior convinced everyone not to seek him out any more. No one asked the drunken shell of man for any favors or wise advice.

Then, unwatched and silent, Bowl Owl began hiding jars of corn seed and beans in the canyon’s secret crevices. He even struggled to write — drawing the petroglyphs on scraps of leather.

Bowl Owl knew that his little pictures were not the true kind of writing. The myths he drew were symbols of ideas. He drew with a cactus needle and his own drawn blood. The foreigners who mocked his writing made letters with their writing. Letters were mere scratches of ink that mocked the sounds that came out of people’s mouths.

So his heartfelt writing was not what alien people called literature. It was blood, it was ideas, it was value, and grand things that had once been alive in the heads of a small people. Maybe with the corn and the beans, that would live again.

In fifty years, the stony pueblo homes would be full of bats and scorpions, the voices of its people forgotten. Nothing but shards of pots and discarded sandals. He had been defeated, and he knew it. All was lost, but maybe something would be found by others.

Somebody else would come back. Time would spiral and bring another people here, some unknowable, strange, future people. People as distant and obscure as the legendary founders of Garden Canyon, Secret Air Base Man and his wife Irrigation Woman.

Before and after Mexico, a canyon people would come back to the canyon. If they saw one stone stacked on a stone, if they saw one image scratched in rock, then they would know that such a life could be lived.

When the singing, cheering migrants marched away, Bowl Owl made it clear to them, with his unkempt head, his soiled robes and his mumbling, that it would be better if he stayed behind. This would be a silent mercy to a good man who had once had some dignity, and had known all the songs. Old Bowl Owl would have a bit of company, too, for the CornWaterMan, who had never left the plaza and never said anything, was still on vigil in the plaza, and still not saying anything.

Bowl Owl offered to look after the great Spiral Calendar for them, all by himself — but they just weren’t having that. That idea was unseemly. If a work of art and craft that magnificent was left behind, people might return on pilgrimage to reminisce about it, or maybe steal it, or deface it. That prospect wouldn’t do. The great calendar had once been beautiful and meaningful, but it was also large and awkward, and in the people’s way.

So they pried it loose from its mounting in the plaza with sharp steel bars. They rolled it straight down the perilous slopes of Garden Canyon. It spun and tumbled, and tumbled and spun, and finally it burst into five hundred pieces.

THE END